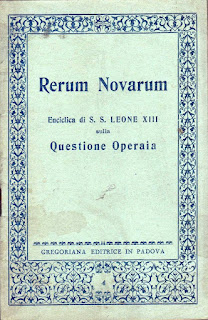

Rerum Novarum, §1-11: A natural law defense of private ownership

As I start looking at Rerum Novarum , Pope Leo XIII's famous 1891 encyclical, I'll first summarize/paraphrase what the encyclical says, paragraph by paragraph, then analyze the way Pope Leo presents his argument, and finally offer my own commentary on it. The first two focus on what is being said, and the last is my own personal response to it. This is a method I recommend to anyone who wants to give an important work a fair reading -- in fact, it's something that I have always tried to teach my students: understand first, and withhold judgment until you are sure you really do understand. This is the whole idea behind the 4-step method of reading with understanding that I’ve propounded elsewhere on this blog. Why start with summary? Because it forces me to boil down the argument to its essential parts — but I don’t want to oversimplify it, so sometimes my “summary” is really more of a paraphrase. I don’t want to skip over any really essential ideas. If you try this