Truth, Eternity, and Mere Facts

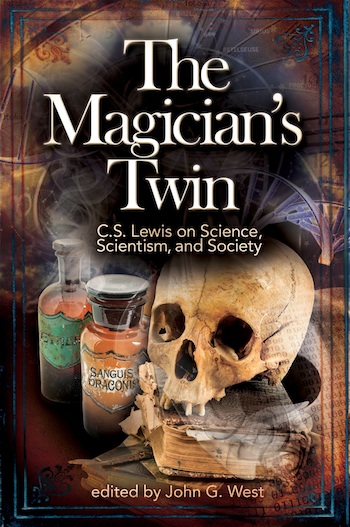

On my way back from a recent meeting of the Dallas/Fort Worth Catholic Writers Group, I caught a snippet of Al Kresta’s interview with John G. West, editor of a new book called The Magician’s Twin: C. S. Lewis on Science, Scientism, and Society. West was discussing the philosophical shortcomings of scientism, an ideology that reduces all truth to that which can be verified empirically. Coincidentally, at our writers’ meeting, I’d just had a conversation with a writer working on a short story that explores a similar theme. This coincidence points to a problem that plagues the modern mind, i.e., the bad habit of confusing mere facts with truth, of conflating knowledge and wisdom. The world we live in today is obsessed with facts, yet has little understanding of (or appreciation for) truth; when scientists claim they know something to be true, we too often take them at their word, never questioning the relationship between particular empirical facts and universal truths. Few scientists are willing to admit the inability of the scientific method to arrive at universal truth (although it can, I believe -- if properly employed -- inexorably approach absolute truth). Anyhow, if you don't believe me, watch this TED talk (since banned from the TED channel for daring to question the dogmas of scientism)by biologist Rupert Sheldrake of Cambridge University. (If you like the video, you might like his book as well: The Science Delusion -- recently re-published under the title Science Set Free: 10 Paths to New Discovery.)

On my way back from a recent meeting of the Dallas/Fort Worth Catholic Writers Group, I caught a snippet of Al Kresta’s interview with John G. West, editor of a new book called The Magician’s Twin: C. S. Lewis on Science, Scientism, and Society. West was discussing the philosophical shortcomings of scientism, an ideology that reduces all truth to that which can be verified empirically. Coincidentally, at our writers’ meeting, I’d just had a conversation with a writer working on a short story that explores a similar theme. This coincidence points to a problem that plagues the modern mind, i.e., the bad habit of confusing mere facts with truth, of conflating knowledge and wisdom. The world we live in today is obsessed with facts, yet has little understanding of (or appreciation for) truth; when scientists claim they know something to be true, we too often take them at their word, never questioning the relationship between particular empirical facts and universal truths. Few scientists are willing to admit the inability of the scientific method to arrive at universal truth (although it can, I believe -- if properly employed -- inexorably approach absolute truth). Anyhow, if you don't believe me, watch this TED talk (since banned from the TED channel for daring to question the dogmas of scientism)by biologist Rupert Sheldrake of Cambridge University. (If you like the video, you might like his book as well: The Science Delusion -- recently re-published under the title Science Set Free: 10 Paths to New Discovery.)Christians know – or should know – that the most important truths cannot be verified by science. These are immaterial, spiritual, and transcendent, metaphysical, literally beyond the realm of science. (Let us not forget that science can observe, and pronounce judgments on, only material and contingent (physical) reality. If it claims to be able to do more, it lies.) Sadly, the modern age has seen a schism introduced between physics and metaphysics, which at times appears to be more of an all-out war.

‘Twas not ever so, however. Earlier ages (one might say wiser ones) understood that there is more to the cosmos than meets the eye, and until the modern era people had no trouble grasping the idea that the immaterial and transcendent is greater than (i.e. truer and more important than) the merely material, because the former is eternal while the latter is contingent and ephemeral. In ancient times, the imagination was often of more help than the naked intellect in grasping such immutable truths. This is why, at the dawn of western culture, poets were considered something akin to prophets; it’s why Homer and Hesiod invoked the immortal Muse to inspire their writings, so that they could adequately convey the truth about their poetic subjects.

Conversely, even fields that today we would regard as matters of fact – history, for instance – had something in common with poetry, in that the facts of the matter were important chiefly because of the universal truths that they bring to light. (Remember that Aristotle acknowledged that history was “philosophical,” but poetry was even more so.) When Livy sat down to compose his history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita, he acknowledged that there was scant documentary evidence for many of the legendary figures and events about which he wrote, but he didn’t necessarily see that as a stumbling block. In the preface to that massive work, he wrote:

I do not intend to either affirm or refute those traditions, more suitable to poetic fables than to authentic historical records, which are handed down from times before the founding of the city or from times just before it was founded. …The traditions he referred to were the legends surrounding the birth and upbringing of Romulus and Remus, who were reputed to be demi-gods fathered by the war god, Mars. After being stolen from their mother and exposed in the wilderness (the “after birth abortion” common in the pagan world), they supposedly were suckled by a mother wolf who heard the

|

| Sons of War God + Suckled by She-Wolf= The founders of Rome were bellicose and savage, like modern scientific dogmatists. |

But, however those and similar myths are considered and judged, I myself will give them no importance. In my opinion each reader should focus attentively on these points: what were the life and customs? Through the actions of which men and by means of what skills, at home and in war, was dominion brought forth and increased? Thereafter the reader may follow mentally how morals collapsed, as is characteristic of a thing sitting idle, little by little when discipline was first slipping, then more and more, then began to plummet, until these times arrived in which we can tolerate neither our faults nor the remedies.In other words, there were moral and civic lessons to be gleaned from this history that transcended mere fact or legend. If Livy had insisted (as a modern historian might) on recording only those public figures and events that could be pinned down with documentary certainty, his history would have been much shorter and of much less value either to his contemporaries or to his posterity.

Mere facts will get lost in the dust of time, but truth will endure.

©2014 Lisa A. Nicholas